L.A. RECORD’s Rena Kosnett conducted what may have been Isaac Hayes’ final interview for us last week. She sends the following obituary:

Isaac Hayes died today, Sunday August 10th, 2008. I had the great fortune to interview Isaac by phone while he was at his home in Memphis a little over a week ago in anticipation of his headlining spot on the upcoming Sunset Junction festival bill. I was ecstatic for the week leading up to the interview, and stayed ecstatic for the week following it, so not surprisingly I received 4 voicemails, 6 text messages, and 9 emails from people informing me of the sad news.

Isaac was a one-man messianic movement who spoke the gospel of groove and spread the sermon of soul throughout American culture. He served to liberate and advocate American funk and human sexuality the way Timothy Leary articulated acid, the way Hunter S. Thompson obliterated objectivism. I was asked frequently after the interview if I had questioned Isaac about South Park or Scientology, and the answer was ‘No.’ Not because I was afraid or felt he would be uncomfortable, but because what was most significant in Isaac’s life—what was most groundbreaking—was his music. For the few moments I had him, that’s what I wanted to stick to.

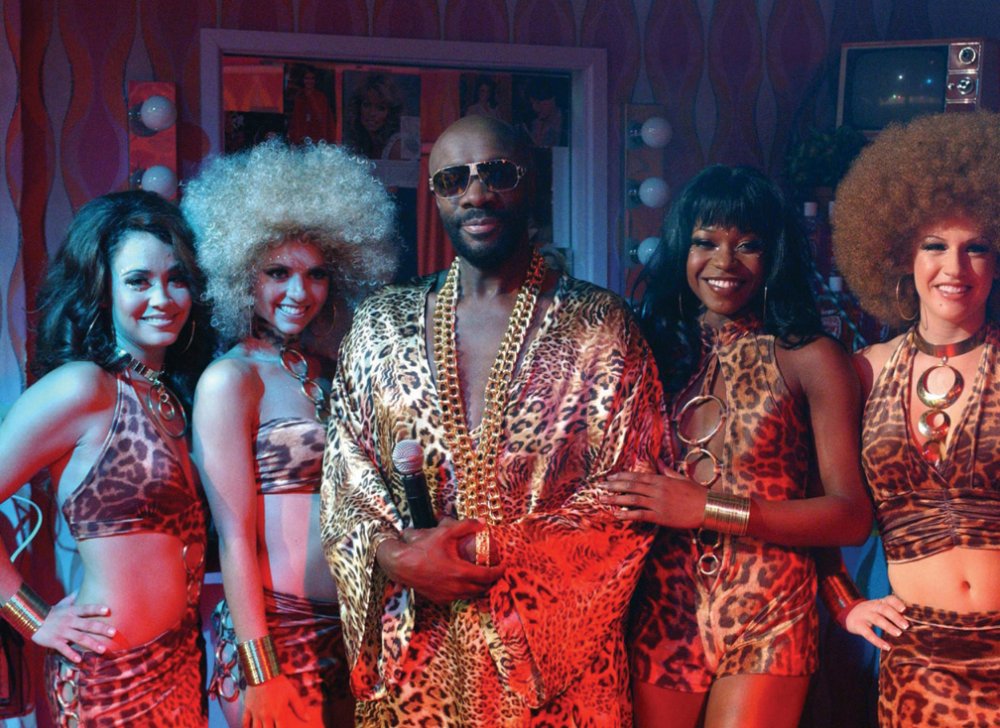

Isaac was self-taught. He was a visionary. He went to the recording studio dressed in gold chains and bright green suits when everyone else was wearing black turtlenecks and gray trouser socks. Isaac worked his way up from being a poor meat packer—even his obituary includes some innuendo!—in rural Tennessee to being the driving creative force behind Stax, which, alongside Motown and Sun, has been one of American music’s most critical labels.

His 1969 album Hot Buttered Soul changed how music was produced, opening soul and pop recordings to more interpretation and spoken interludes, and paving the way for Barry White’s and Millie Jackson’s silky mid-song eroticisms—now a staple, and indeed nearly a cliché, of R&B music. But even before Isaac’s throaty classics made it to the turntable, he was heard on the airwaves through the voices of Sam & Dave, Otis Redding, and Carla Thomas. Isaac, mainly with his creative partner David Porter, wrote the hits “Soul Man,” “Hold On, I’m Comin’,” “When Something is Wrong with My Baby”, and “Soul Sister Brown Sugar,” among others, and his orchestral, horn, organ, and bass scores inspired the soundtracks for countless films, blaxploitation and otherwise.

What struck me most during our interview, despite the clear struggles he was working through due to his 2006 stroke, was his exaltation. He was excited about playing the Sunset Junction, excited about his new album, and gracious with his laughter, time, and his unmatched ability to serenade. Even through a cell phone headset, hearing him sing made me swoon.

We have lost our Soul Man, our Black Moses, and his deep voice and deeper vitality will surely be missed.